When examining the field of veterinary medicine and its racial diversity proportions, it is most important to begin with the facts. A clear racial disparity exists within this profession, as evidenced by the significant percentage of White student practitioners. However, at the local level, other differences are apparent.

To better understand how this racial disparity may represent the general population numbers, it is necessary to consider other conditions. It is noteworthy that this profession remains most lucrative in areas of higher income, which tend to be predominantly White. Therefore, it may be assumed that this study has more value to Whites, given the high-income potential and sense of affluence it brings. Of course, veterinary study requires other qualities, such as personality and a general sense of interest or passion for a very specific type of work.

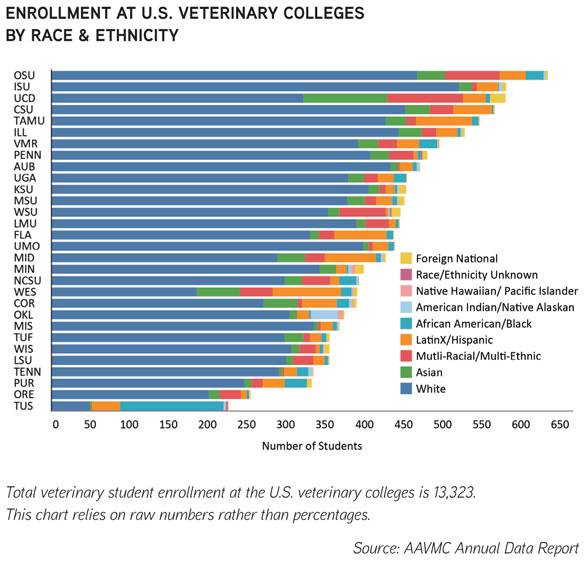

This dichotomy presents numerous areas for discussion, including the growing diversity in minority communities themselves. The first chart below displays the racial numbers for various veterinary colleges, revealing a preference for traditional values when it comes to race matters. Tuskeegee University (TUS), for example, has a greater proportion of African American/Black students, as it has had in other areas of study for years. However, it still maintains a relatively balanced student population of White and LatinX/Hispanic students, rather than a reverse outlook as a whole.

In spite of the statistical data and historical evidence of male dominance in the veterinary medicine field, it is imperative to further investigate gender disparities, as there is now a surprising and significant gap between female and male veterinary students. In the United States and Canada, women currently make up 80% of the veterinary student population, outnumbering men to such an extent that men are increasingly less likely to even apply to veterinary school.

Between 1985 and 1999, the percentage of male applicants to veterinary colleges decreased from 44% to 28%. This decline may be attributed, in part, to external social factors. It is worth noting that veterinary doctors have higher rates of suicide compared to all other professions, except for police officers. This may be compounded by the overwhelming debt-to-income ratio resulting from the increasing cost of education loans. Shockingly, 10% of veterinarians who have passed away since 2010 have died by suicide.

Another contributing factor to this trend is believed to be a lack of male interest in the field’s growing reliance on corporate entities in veterinary medicine. More and more veterinary practitioners are employed by corporations or operate under the influence of corporate interests, which often entails demonstrating brand loyalty and dependence on practices that may not always be well-received, particularly in terms of hygiene and feeding practices.